During a radio interview, someone called in and asked me for a recommendation on a good English translation of the Hebrew Old Testament. The caller said she wanted to go back to the ancient roots of her faith and thought reading the Hebrew text was the way to go. My answer probably surprised her.

During a radio interview, someone called in and asked me for a recommendation on a good English translation of the Hebrew Old Testament. The caller said she wanted to go back to the ancient roots of her faith and thought reading the Hebrew text was the way to go. My answer probably surprised her.

I told her that if she wanted to get back to the “old-time religion,” she should use the Scripture that Jesus, St. Paul, and the writers of the New Testament most commonly used, but it wasn’t Hebrew. It was Greek.

Greek? Wasn’t the Old Testament for the most part originally written in Hebrew? Didn’t the New Testament rely on the Hebrew Old Testament? To answer this, we need to take a closer look at what’s going on behind the Bible.

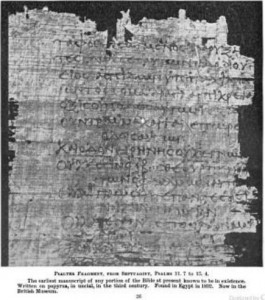

There were a number of different Old Testament texts in circulation in the first century. Some were written in Hebrew, while others were translations of the Hebrew into Aramaic and Greek. The one text that the writers of the New Testament appear to have favored more than the others is a Greek translation known as the Septuagint.

The Septuagint got its rather odd name from a story found in the Letter of Aristeas that relates how 70 (perhaps 72) Jewish scribes were commissioned to translate the Old Testament into Greek during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 B.C.). According to the story, these 70 scribes worked separately on their translations, yet they miraculously translated the exact same thing, word for word. Hence, it is called the Seventy, which in Latin is Septuagint (or LXX for short).

Although the New Testament used texts other than the Septuagint, it certainly quotes from it more than the others. In fact, the Septuagint makes up about two-thirds of the approximately 300 Old Testament quotations made in the New Testament. Some of these quotations are quite important.

Perhaps the most famous New Testament quotations from the Septuagint is found in Matthew 1:22-23, where it says of Christ’s birth, “All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: ‘Behold, the virgin shall be with child and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,’ which means ‘God is with us’” (Isaiah 7:14 LXX).

What’s significant about this quotation is that the Hebrew text that has come down to us gives a rather general word, usually translated “young maiden,” instead of the Septuagint’s “virgin.” Of course, young maidens can be virgins (as normally would be the case), but the word doesn’t have that specific of a meaning. This difference, I believe, highlights the real value of the Greek Septuagint for understanding the New Testament and first century Judaism.

What’s amazing about the Septuagint is that it can function as a snapshot of how the Jews understood the Hebrew text hundreds of years before the time of Christ. Remember, the Septuagint was translated some time before the late second century B.C. When the translators came across Isaiah 7:14, which Matthew quoted above, they translated the word as “virgin” showing that in their day the “young maiden” of Isaiah 7:14 was understood to be a virgin. Matthew, therefore, understood that Mary’s virgin birth of Jesus was the fulfillment of Isaiah 7:14, as it was understood in pre-Christian Judaism.

Much later, around the middle of the second Christian century, when rabbinical Judaism adopted a Hebrew text to be their norm, they rejected the Septuagint. But Christians continued to use what they’ve always used, the Greek Septuagint.

So if you’d like to get back to that “old time religion,” you’d do what Jesus, the Apostles, the New Testament writers and the early Church did; you’d go to the Septuagint.

(published by the Michigan Catholic Newspaper http://themichigancatholic.com/